Making and doing anthropology, archives and people-places in Arnhem Land (and in Canberra?)

I start this piece with a question for you, my reader: Do you need your own anthropologist?

This was a question I posed to conference participants who interacted with my Making & Doing display at AusSTS 2024. I wonder if any attendees had ever considered that they might ‘need’ their own anthropologist – someone engaged by them to do something for them that only ‘an anthropologist’ can do? Certainly several of those present (like many in the world of STS) have a foot in the discipline of anthropology. But many experienced my injunction to become a figure who commissions an anthropologist as incomprehensible.

I use this question as a launching point here because it introduces the problematic around which I attempted to compose a display of Making and Doing STS knowledge. This display revolved around my participation with a group of Indigenous Elders living in the town of Maningrida on the north coast of the Northern Territory. These Elders are speakers of five different languages from the saltwater regions of central Arnhem Land. We have been collaborating in practices of ‘contemporary doings of Indigenous Country’ since 2023, a process in which I have consistently been labelled by the group as ‘our anthropologist’.

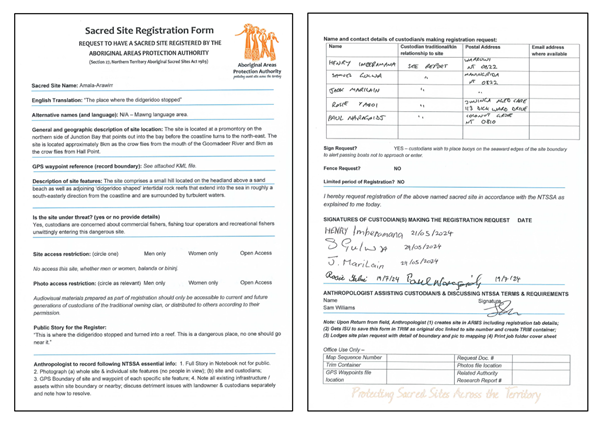

The M&D display I designed consisted of a profusion of objects that when bundled together might be called an ‘archive’, albeit nascent and multiple in the sense that the presence of several provenance streams are evident from several diverse institutions. Consisting of videos, photographs, maps, reports and a ‘Sacred Site Registration Form’, the display demonstrated the inadvertent and haphazard generation of this archive. Together, these objects constitute records of a contemporary moment in the ongoing collective life of numerous people-places in Arnhem Land. On one November day in 2024, they were recomposed in Ngambri/Canberra as both performance and inquiry.

As a relative newcomer to STS, and first-time presenter in a Making & Doing session, I was both excited and apprehensive about the possibilities afforded by this format of institutional knowledge sharing. I felt aware of the risk that the display might be interpreted by conference participants as some sort of ‘authoritative’ anthropological account of an Indigenous ‘other’. I found myself drawn to STS precisely because I had become unsettled by the authoritative voice of some anthropological research. At the time I found it hard to describe this uneasiness, but might now articulate this as a desire to find a mode of inquiry that (1) configured me as a knower in a way that attended to the practices of collaborative research with Indigenous Elders; and (2) made sense of the way these Elders positioned my work for them as ‘their anthropologist’. This was squarely not as a participant observer and documenter but as someone delivering generative politico-economic outcomes which serve the purposes of several constitutive elements of an Australian First Nation polity, by doing technical work on their behalf.

The effectiveness of my M&D display, therefore, seemed to pivot on how apparent it was that this display should not be interpreted as a representation of knowledge practices, but rather a (re)performance of the knowledge practices of situated institutions, which fundamentally also includes the institution of anthropology / ‘the anthropologist’. Unlike the ordinary ‘stand-and-talk’ type of conference presentation, M&D seemed to evade the possibility that I (as anthropologist-researcher) hold authority or expertise to speak on behalf of the people-places that are the subject of our collaboration. Because the M&D display is open to cultivation of indeterminacy and facilitates (re)interpretation, the conference participant who approaches the table has a far more active and critical role as a knowing body who must do work, than do the audience members in a lecture theatre (who in an STS sense are merely “modest witnesses”) (Shapin and Schaffer,1985:20; Haraway, 1997:3).

I was curious to see which parts of the archive might draw the attention of those who approached my M&D display in the melee of the foyer. Consisting of so many different components (videos, photographs, maps, reports, forms), the archive on show was deliberately cacophonous, each object contributing a sense that there are a multitude of practices at work in the performance of these people-places both in situ in Arnhem Land and in the setting of the conference. Which of these might prompt the engagement of a conference participant?

In narrating this account of Making & Doing STS knowledge, I want to fashion a story around two components of the archive that became the focus of several conversations during the two-hour AusSTS 2024 Conference session: a video, and a ‘Sacred Site Registration Form’. In placing these two very different objects side by side here, I hope to elucidate something of the practices-in-practice at work in the curation of the display.

The five-minute video showed Indigenous Elder Samuel Gulwa speaking to the camera in Mawng language for a few minutes. He then sets a pandanus tree on fire with a cigarette lighter before calling out in a loud voice while looking away from the camera. The video cuts to Samuel sitting alongside another Elder, Henry Imberamana, as Henry speaks to the camera. This time, the Mawng language speech is subtitled. The subtitles read, “That place Yilomurlk, that’s Dhuwa country. It goes up to Miwil. Then after that it’s Yirridjdja. Yirridjdja up to Inamanyjarr-Wilam and Duka Arnawu. Yirridjdja all the way round to Mawuludja. Yirridjdja country for Manyjurlnguny people.”

More than any other aspect of the archive on display, the video acted as a tool to deliberately disorient the viewer. These practices – which are this people-place – are incomprehensible for most viewers. To the conference participant, the video states loud and clear ‘You know that you don’t know what is going on here’. The video asks the viewer to watch someone they don’t know, speaking a language they don’t understand, doing something they’ve never seen done before. If anything, the English subtitles (which were added at the instruction of Elders only to certain parts of the video) only obfuscate further: one might be able to read the words and understand the sentence structure, but the names are foreign and the meaning unclear.

In its illegibility, this video undermines the notion of knowledge as representation. The video is very evidently the performance of the knowledge practices of a situated institution. As an archival object, the video makes a claim: that this situated knowledge does not travel easily. Presenting a video like this in a conference display felt uncomfortable to me – shouldn’t I give the viewer some more assistance in the form of context, explanation or background to make sense of what is going on here? But I found those who engaged with the display surprisingly willing to watch for 5 minutes with the headphones on, sitting with the feeling of knowing that they didn’t know.

The ‘Sacred Site Registration Form’ offers something of a counter to this video. On the first of two pages, the form details several points of information required in order to fulfil a “Request to have a sacred site registered by the Aboriginal Areas Protection Authority”. Among other things, these data categories include the name of the sacred site, its geographic description, GPS coordinates, and access restrictions. The heading of the form names a portion of a piece of legislation – “Section 27, Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989” – that presumably undergirds the content of the form or provides some legitimation for the data categories requested.

On the second page of the form, we see the names and signatures of the “custodians making the registration request”. Among these are Samuel Gulwa and Henry Imberamana, the two men speaking Mawng in the video on display. Below their signatures is a section for the “Anthropologist assisting custodians” to write and sign their name – in this case me, Sam Williams.

As I interacted with conference participants over the M&D display, several people asked about this form. What was its purpose? What did it mean to ‘register’ a sacred site? What was a sacred site? Those who had seen the video began to make connections – the burning pandanus tree set alight by Samuel in the video was the same pandanus tree written about in the form: “The site consists of two stands of pandanus behind a sandy beach … Traditional owners can burn the pandanus here and call out to their ancestors to calm the winds and rough seas”.

Where the video is illegible and disorienting, the form translates this people-place into a point of identification as a soon-to-be-registered sacred site. The role of the named “Anthropologist assisting custodians” appears to be central to this translation. If the video performs a situated knowledge that does not travel easily, the form – through the work of the anthropologist – makes knowledge travel by translating people-place into data categories to fulfil the requirements of the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989. The form is a technoscientific object in which the role of the anthropologist is configured by certain practices that constitute some form of technical work.

I return to my opening question: ‘Do you need your own anthropologist?’ I was commissioned by Samuel, Henry and other Elders in Maningrida as “our anthropologist” to undertake a body of work they considered both important and generative. Every object in the archive on display was an outcome of this collaboration, including both the video of Samuel burning the pandanus and the work of registering this place as a sacred site. These two objects appear to present knowledge about the same people-place: a stand of pandanus in Arnhem Land which may soon be a registered sacred site. And yet, in their extreme difference the two objects hold a tension, a “trouble” to use Haraway’s (2016) language, around the politics of ambiguous translation in which the anthropologist stands as a central figure. In some way, both objects do the technical work of showing that Mawng speaking Indigenous Elders own this people-place and it owns them. But where the video shows this by making knowledge deliberately illegible, the form is a technology of creating legibility. These are two technoscientific objects stemming from wildly different epistemic commitments: one that insists that knowledge cannot be disconnected from the place; the other that functions as a technology to disconnect knowledge from place.

In talking with and about these objects at the conference – and through conversations vacating the space between the video and the Sacred Site Registration Form – I felt this tension increasingly acutely within my own body. How am I (as an anthropologist) constructed in practices by these two institutions: the Indigenous clan and the Northern Territory Aboriginal Sacred Sites Act 1989?

And in writing down this account of the M&D display, I see this text as clarifying a partial answer to this question that was not fully apparent to me at the time: As a knower, the anthropologist as simultaneously ‘authored’ and ‘authorised’ by those radically disparate contemporary institutions is a loosely bundled multiplicity. Rather than making certain information about people-places in north central Arnhem Land travel to Canberra in a format that was comprehensible to conference attendees, the M&D display created a stage for something else. Necessarily speaking as an embodied knower, a singularity in a here and now. I was insisting to anyone who would listen: I might look like a singular but if you listen carefully, you will hear that I speak with a ‘forked tongue’. I was seeking to effect an experience of epistemic disconcertment in the audience. In this sense, the archive on show was not about displaying information about a research site or showing solutions to a research question, but rather angled toward evoking an experience of discomfort arising from recognition of ontological multiplicity as knowers.

So, what follows? Is epistemic duplicity a problem? For whom (apart from the disconcerted speaker-writer) is it a problem? and Why? Or ‘where’ is it a problem and where is it an epistemic resource.