Knowing through embodied data materialization

Top-end STS is an academic collective based at Charles Darwin University in Australia’s Northern Territory. This collective has inspired and continues to inspire me in its insisting on understanding how science and technology embedded in particular institutions and environments make knowers and knowledges. The collective is deeply concerned with how knowers and knowledges are made, yet the approach is very far from social constructivism. There is not in this onto-epistemology a knower, an ethnographer for example, studying a phenomenon to make it known to audiences in different times and places. Instead, the knower is made in a here-now and folded into everything that goes on, while at the same time being made through other here-nows. It is a practice-based approach, but not because practices is where social action and interaction can be studied as in much practice-based research. Top-end STS attends to practices because they are where experiences congeal, and categories harden.

Can a designed data object offer a working model for knowing ethnographically and collaboratively and thereby problematize the notion of the individual as knower? Can ethnographic materialization conjure up a knower whose ‘knowing’ is socially, institutionally, situationally, environmentally, historically configured all at once while at the same time experience-based? In this essay I offer examples from my own aesthetic research practice as a pathway into these questions to inspire methodologies that accept individual experiencing and knowing to be socially, materially, culturally and historically configured in here and nows and that use this insight to loosen up hard categories.

To get a handle on such a distributed yet situated knower, it is useful to think with the concept of people-place developed by Helen Verran with David Turnbull, Michael Christie and others to initiate a discussion on alternatives to established ways of thinking about the relation between people, culture, and history and locality. The ‘drawn together’ conceptual in(ter)vention of ‘people’ and ‘place’ enacts how the making and embedding of all kinds of knowledge happens in specific times and places. The concept also highlights how knowledge-making can be afforded by places because places are social through and through.

Verran and colleagues did not accept a disconnect between place and people that would then allow anthropologists and others to join up the two categories again (Verran, 2025). People-place to them is pre-existing social action, and about cosmologies, materialities, politics, processes, and power relations. But, before those it is first and foremost about knowledge (epistemic practices).

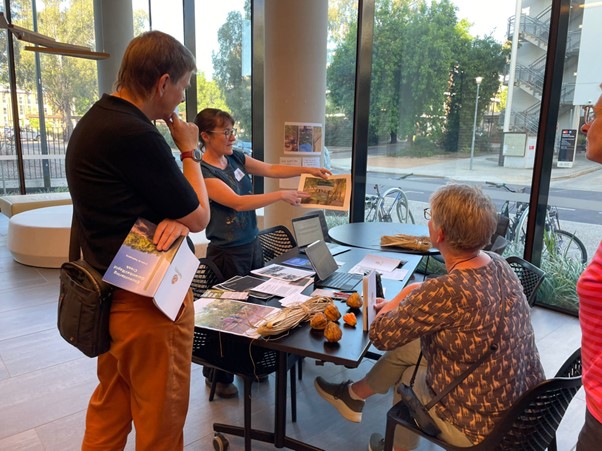

Various design objects were exhibited at the Making & Doing session during the 2024 Australian STS meeting in Canberra (Kamberri). These objects problematize a figure of the individual knower who ‘is’ prior to the act of knowing. Some of them would speak to issues of epistemic agonism like demonstrated in the short movie of a wild-life camera put up and controlled by Aboriginal elders exhibited by Michaela Spencer. Part of the installation was also an undersea video of catfish that never showed up in the video, but was vividly present nevertheless. The installation shows that researcher participation in people-places is configured by access to knowledge making practices. The installation invites you to consider what competent scientific participation in knowledge making practices might be. The installation invites the visitor to consider how researchers are always are always both invited into, and thus part of, and declined access to collaborators’ practices. And to reflect on how their own knowledge making is relational, experience-based, and extended in time and space through particular networks and materialities.

This speaks to the installation I brought to the conference’s Making and Doing session. In my research, I have often resorted to ethnographic materializations to try to build connections to worlds that are hard to access. Renewable energy innovation and engineering and the elements that are involved in this such as ocean waves, for example (Winthereik et al., 2019). But what began as a keen interest in how materials can help researchers in accessing the unfamiliar, for example the world of doctors (Winthereik et al., 2002), developed into an analytical-theoretical endeavor (Ballestero & Winthereik, 2021). We here consider materialization as a way of tapping into experimental situations that is both constraining and rife with possibility. Materialization or ‘aesthetic methods’ offers pilotage for practicing individuality in collaboration, and thus for competent scientific participation and knowledge making as advanced by Top-End STS.

Accessing digitalisation

How to do research on a phenomenon that is at once inclusive and excluding of you and your knowledge making? One that offers you full access and keeps you at an arm’s length. I am here speaking of the on-going digital transformation of welfare states that has replaced employees in the frontline of the public sector with self-service platforms for communication between state and citizen. A transformation that has a democratic dark side to it that is worth investigating (Collington, 2022; Winthereik et al., 2024). How to make sense of “digital welfare?”. At one and the same time being for all citizens and residents and excluding 22% of the population (Digitaliseringsstyrelsen & KL, 2021) due to overly standardized technical ‘solutions,’ and homogenizing ideologies (Carreras, 2024).

Marilyn Strathern in Partial Connections (Strathern, 1991) speaks of persons as ‘dividuals’ (as earlier on did Nietzsche). Thus, the ‘undoing’ of the individual has a history. But when it comes to materializations of state-citizen relations the individual stands undivided. Concretely this means that from the age of 15, in Denmark, the citizen is on their own, bounded, singled out, in relation to state matters. Of course, this is not just an effect of economists and computer scientists’ tendency of redoing the world through models and modelling, it is also an effect of human rights and of the legal autonomy granted to citizens of liberal, democratic states. Things that we do not want to be without. The problem, however, with the individual’s inviolable right to in-dividuality in this specific context is that it does not work in practice. Unless of course, other things like equal access to welfare services, are violated. One serious aspect of the problem is that the trade-off between promoting citizens as individuals over equal rights to welfare services has taken place without democratic deliberation (Aagaard & Jæger, 2025). It is an instance where the design of government information systems subtly and without anyone noticing it replaced democratic negotiation (Pelizza, 2016).

A dress to access the digital welfare state as people-place

A dress made of analogue-digital identification cards has helped me access digitalization in the sense put forward by Michaela Spencer, and better relate to them as people-places, that is as places where interwoven cosmologies, materialities, politics, processes, and power relations shape ways of knowing and doing people.

Ethnographic research affirmed an initial hunch that the digital welfare state is inefficient in seeking to enroll everyone as ‘users’ in more or less the same way (Carreras, 2024; Carreras & Winthereik, 2024) as it produces forms of exclusion that require new kinds of stake action. The municipalities have been tasked to take steps towards including the excluded citizens, for example. Digital inclusion has become a policy concept. To me, participation in this situation has included 1) to engage in the public debate on public sector digitalization, 2) through activism by setting up a network of practitioners and other experts to develop principles for citizen-centred digitalization that were presented to the Minister of Digitalization and Equality, and 3) to materialize state-citizen relations differently. The latter involved the making of a dress.

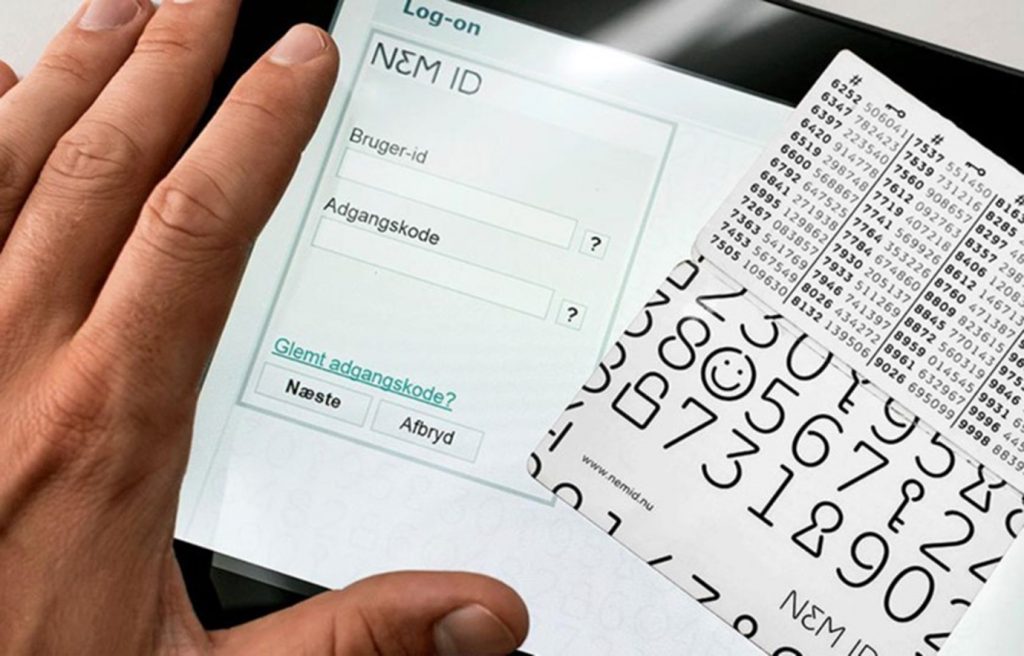

The core material of the dress is a laminated paper card with numbers on it. It is the physical component of a login solution whose official name is ‘NemID’ (literally: ‘EasyID’). It came into use in 2010, but it was not until 2013 when digital mail became mandatory for all citizens and residents in Denmark. NemID became the sole means of citizen identification vis a vis the public authorities and framed the citizen as an individual in at least two ways. First, as an entity whose legal autonomy would stand above all other identities that the person has. Second, as an entity whose actions as a user of public services was both crucial for the operation of the welfare state (as digital self-service was introduced to save money), and de-coupled from it (as in-person support in the administration was removed to save money).

Each key card contains 132 ‘keys’ presented as rows of numbers, or codes, some of them in bold. Key cards were sent by physical mail to every citizen as well as to private companies. Citizens were allowed up to three cards, companies many more. Citizens could apply for an exemption to use digital mail, but not the key card. Specific criteria applied that were not easily fulfilled. A token, a kind of key chain, was available as a more accessible solution for some user groups. New cards or tokens were sent as the ‘keys’ on a card were gradually used up. Each ‘key’ could be used only once.[1] To log on to a government web site a person would need three things: 1) A user ID. 2) A password and 3) A key card. Secure access worked through combination of what the person ‘is’ (marker of affiliation), what the person ‘knows’ (password), and what the person ‘has’ (a code on a key card or a token that works through a digitally generated four-digit code). In 2023 the NemID key card was taken out of business because it wasn’t considered secure enough by the financial sector.

I began collecting used key cards in 2020 when I became aware that this mode of identity verification would be terminated. There was no other purpose for me in collecting the cards than a sense that I would like to use them for something, because the cards were nice, a token of the digital welfare state, and they were disappearing. Inspired by the pill dress, a dress sewn of the pills taken by a chronic patient during a lifetime, I began dreaming of sewing a dress of the cards. I badly wanted to materialize a digital welfare state that could be felt and touched and related to in other ways than as an individual in front of a desktop computer as in this image from one of the many state reports advocating for the benefits of state digitalisation.

I have described the production of the key card dress elsewhere (Winthereik, under review), and the thinking behind its design, so will not delve into these reflections here. Instead, I will first comment on what knowing through embodied data materialization may help us understand about state-citizen relations after digitalisation, and then return to the question of how the dress as a materialization of embodied data helps us develop methodologies for knowing people-places.

Creating an artifact that stiches together individuals by making an unfinished whole out of unique identification cards and wearing it, conjures up a digital state. This digital state – unlike its counterpart – is not made of individuals with inviolable rights and a duty to contribute to the smooth functioning of digital services through computerized actions and data. It is made up people who use the cards to live their lives. They form a stitched together sociality, have overlapping needs and they borrow a little from each other as they seek various kinds of support from each other, including digital support.

Continuing to the methodology aspects: To know people-places and their epistemic practices entails offering one’s own experience as part of the assemblage. Like the non-present-yet-present catfish in Michaela’s video performed the audience as participants and co-workers in figuring out a complex situation, the dress is an invitation. Its (2023) design has grown out of experiences from inside the digital state. Making it, wearing it, and showing it thus becomes a way of re-experiencing their experience. The dress asks about exclusion and inclusion and of affective worldly embodied digital practices and knowing.

As ‘dead’ material, the cards have been re-materialized and part of a different ethnographic experience of digitalization. Aesthetic methods invite us to know the world differently and connect then-theres with here-nows (Cadena & Blaser, 2018). Fieldwork, analysis, learning and knowing can no longer be kept apart. Some consider this lack of rigor (Hammersley, 2022). I prefer considering it an opportunity to re-vitalize one’s thinking and raise new questions.

“While anthropology has privileged anthropologists’ experience in the field as a source of insight, ethnographic experimentation locates the experimental devices as the source of knowledge-making”, argues Estalella and continues: “In this process, the field progressively loses relevance (…) its place is taken by the experimental devices – what I call field devices – that arrange the conditions for the empirical encounter” (p. 3).

Based on my experiences of making and doing the NemID dress, it is not only that the field loses some of its stability, but it is also revealed to be an artifact of analysis rather than a thing ‘out there’. Therefore, the competent scientific participant must reveal herself as also a responsible collaborator in conjuring up and making space for the multiple and co-existing realities of any people-place. Productive encounters do not take the form of posing or answering questions, but of walking together allowing familiar landscapes to present themselves in new ways. In this process, materialization techniques offers constraints and possibilities so that we are made to engage in thinking together.

[1] In 2023 NemID was fully replaced by MitID (literally MyID). MitID is only available as an app and requires that the citizen has a newer smart phone.