Making and Doing Guramabai/Rapid Creek and AusSTS

How are creeks and modern universities entangled? How might STS Making and Doing help with loosening some of these clotted relations? And might this open possibilities for new kinds of epistemic institutional routines?

This video was taken by Leonie Norrington, one of the members of our TopEndSTS collective. She first sat down on the riverbank, and from their plunged her hand into the water trying to get some good underwater shots with a new GoPro. The technology was new and at this point rather cumbersome, but the footage she took invites you under the water, and into the slightly murky flow of Gurambai/Rapid Creek. Just after this was taken, Leonie decided the shots needed to be more immersive, and jumped in, clothes and all. I saw the water close over her head before she came up laughing.

In ‘messing about’ in Gurambai/Rapid Creek, TopEndSTS have been worrying away at the relations between creeks and universities for some time now. We initially had no formal warrant to be carrying out the work that we have. But we have had an ongoing interest and commitment to learning appropriate forms of conviviality in being involved as STS researchers in the life of this ‘watery place’.

Gurambai has always been a Larrakia place. This is where Old Man Nungalinya lay down, and his wife Binybara lay down next to him. The ancestral creators made this place as they walked the land, got tired and lay down. Where the Old Man placed his elbow is where freshwater now flows. Larrakia people are this place, and have always danced, sang, spoken its existence.

Rapid Creek on the other hand, is entangled within naturalist ontologies enacted in the work of conservationists and land managers working to manage the native ecologies, invasive species, fire and water of Rapid Creek. It also caught up within development logics which have engineered the airport next door, the hotels which skirt the creek, it’s walking trails and the current flow of the watercourse.

It is these second of these – ‘Rapid Creek’ – which is much more familiar to us as TopEndSTS has involved ourselves in the everyday life of this people-place. It is this modern figuration of the creek which brings with it familiar and active politics of contestation between differing parties, waged in a variety of ways. However, an active (cosmo)politics is less readily engaged. Part of our ongoing task in being involved in this place, is to be tuning up ways in which we might work as a cosmopolitically sensitive (in)competent knowers being constituted amidst differing ‘knowns’ in the making. This is quite a difficult positionality to work our way into, and even harder to hold steady. But in paying attention to stops and starts which we encounter in collaborations, we are frequently pulled up short as we bump up against certain undisclosed norms and commitments within the collective life of Gurambai/Rapid Creek.

As our work with the creek has gone on, we have been fortunate in gaining funding to support more active collaboration with those who are likewise entangled in the life of Gurambai/Rapid Creek, working to make visible different knowledge traditions, their data practices and their epistemic concepts. Sometimes this has been working as researchers funded on our own project funded by the Australian Research Council, and at other times being contracted to develop GroundUp monitoring and evaluation of an Urban Waterways project gradually finding its way at Gurambai/Rapid Creek. Early meetings and engagements around this work have been interesting, and seem to have ‘outed’ quite different commitments within the epistemic practices (also done as institutional routines) within these various groups as we’ve sought ways to collaborate. I offer a few brief stories of these beginning collaborations; two of false starts and one of tentative stepping forward.

i. Missing our meetings with CDU hydrologists

We had been trying to meet to of the hydrologists who were doing a lot of water monitoring work at Rapid Creek. They were initially very happy to chat, but when we tried to get together, finding a time to get together proved elusive. Given everyone’s time pressures, one of the hydrologists suggested he could send a brief rundown of his concerns about the Waterways project, so a meeting wouldn’t be necessary. This was not why we had wanted to meet, but his objections were nonetheless interesting. When the project was beginning, there were a full two and a half days of talk before questions about what we already know about the functioning of these water systems even started to be asked. Working with discipline experts early would have been advisable, and helped to set up a design that made sense. However, this wasn’t what happened and when a decision was made on the project design and funding distribution, this was made in his absence, in a way that didn’t make sense, and with the most significant proportion of funding being allocated to a Larrakia ranger group. He was still very interested in the project, but remains worried that an opportunity was being missed.

ii. Being asked to pause by the Airport Development Group (ADG)

We had also been hoping to have a chat with the environment manager of the ADG. This organisation owned and managed significant areas of land around Rapid Creek. They controlled the airport next door, and manage two airport hotels nearby. Part of their responsibilities include the management of the bushland and riparian environments in within the boundaries of airport lands. As part of funded CDU research work engaging multiple parties to an urban rivers project, we sought an informal meeting to learn from the ADG what might be of interest or benefit to them as we also work with others along the creek, learning about their expert management and care practices. Again, we tried for this meeting on several occasions, but were finally refused on the basis that the ADG could not speak with us until they had an MOU in place with the university, and ‘better understood the ecology of our organisation, including why, how, and where information is used, and to what intent. Until then, we will not be volunteering any information outside of our official channels’. As in the engagements with the hydrologist, we were a little taken aback here, as we had not been intending to be talking about ‘data’ at all. However, this was very much the focus of this group, here and in other settings, with the value of their own, and others, data sets being of significant value to the organisation and their practices, it seems.

iii. Being cautiously guided by Larrakia Elders

Donna and Lorraine are Larrakia Elders who have spent all of their lives along Gurambai/Rapid Creek and understand themselves to be custodians for this place constituted by the Ancestors as they walked. They have always been very careful about when, where and with who they work, particularly around anything concerning Larrakia knowledge of this place, and how it is danced, sung and told in stories. 20 years ago, they pulled out of a project with our team for this reason, but when approached more recently, they were still wary but also interested. ‘Perhaps now is the time’, Lorraine suggested, that we could work with CDU again. She had been working at CDU for many years on other projects, but when working with Gurambai/Rapid Creek was different. We would need to go slowly, and nothing would be shown publicly without permission. It was in this mode, that we have started tentative steps, following Lorraine and Donna’s lead. They have begun experimenting with drones, camera traps and audio recordings in bringing to life forms of sensings which perform the right relations of knowers and knowns in voicing Gurambai/Rapid Creek and how such performative sensing might be made visible and perhaps partially connectable with those of others.

I tell these stories here because in different ways I see the human participants within them as all trying to grapple with the question ‘how creeks and universities entangled?’ And these grapplings involve politico-epistemics. In the first, the university as a home of disciplinary expertise was somewhat disconcertingly being pushed aside. Here, means for structing water monitoring designs were not being worked out in accordance with hydrological disciplinary practice, and the cognitive authorities routine epistemic practices by which these relations are supposed to flow. In the second, the university is not seen as having disciplinary expertise at all but rather becomes just another organisational competitor in an environment where data was both costly to produce and valuable to hold. Here grounded practices of collection didn’t seem to matter as much as the accounting for the location and protection of data sets in professional partnerships. Then in the third, it sems that what the university might be and what it might do is itself an open question, and one requiring any potential collaborators to have to leave aside their preconceptions and start to develop new routines for suitable collaboration under Larrakia authority and in-place. In the first two cases, we seemed to be being interpolated into roles assumed as already existing. In the third there was no role we needed to fulfill, but there was a definite accountability which we were being called to respond to.

***

As TopEndSTS our response to these different figurations has been to go to ground and focus on the practicings of epistemic practices. That is, to begin in place being attentive to these moments, of stoppage and disconcertment where who we are and what we’re supposed to do seem somewhat in doubt. We want to hold open the possibility of ongoing re-negotiations in the performance of collective practice in the here and now, together. However, these three sensitising accounts above also alert us to already clotted and accreted habits of practice and collaboration established in the setting and situation of this creek, and its ongoing collective life. They point to the presence of already existing norms, as well as possible openings, relevant to ongoing collective work negotiating and navigating complex in-place conceptual relations of knowers and knowns, and the institutions that attend them.

In reflecting on our own emerging work in this vein, I tell three more stories, each concerning the entanglements of creeks and universities in three different settings. Putting ourselves down in-place, and sharing these stories, I hope I can nurture means for feeling a way into situated entangled relations of Gurambai/Rapid Creek in the here and now.

i. At the creek

We’re sitting with our toes in the water and pencils in our hands. This moment captures in the picture was part of an all-day event initiated by TopEndSTS as part of a ‘field school’ we had initiated as a means of involving ourselves in the everyday practices of Gurambai/Rapid Creek, and the means by which it enacts itself. We weren’t too sure how to do this, but different members of the group initiated small exercises or events, such as this one led by Kelly Lee Hickey. Here she asked us to engage in an activity she had adapted from Linda Knight called ‘inefficient mapping’. There were small fish swimming about in the pool where we stopped. Watching the fish and their movement with and against the water flows, we were to trace their trajectories on the paper. We wouldn’t look at the pencil, but as our eyes followed the fish, we would allow our hands to be drawn by their movement. When we reached the edge of the page, we would stop, pick up another fish, and start tracing their path. This was one of many other activities, where we listened for the sounds of military aircraft, practiced slow walking, collected fallen nuts and seeds, followed butterflies, reflected on our participations, told stories, retold histories and made video and audio recordings. Participating in the knowings of the creek as practices being done, and sometimes redone.

ii. At NARU

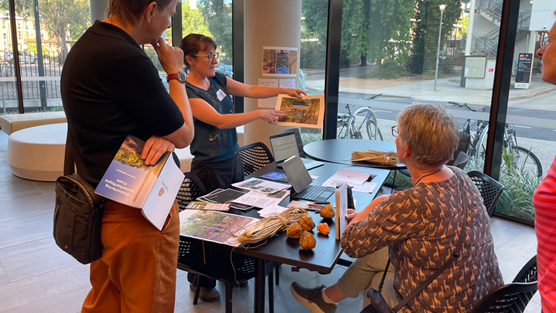

Through the good graces and canny grant writing of TopEndSTSer Kirsty Wissing, we were fortunate to host a preparation event in the lead up to the Making and Doing session at AusSTS 2025. The setting was the Northern Australia Research Unit (NARU) an outpost of ANU, where we were able to spend a full day trying out our M&D presentations. The format was unfamiliar for most, and the presentations that we were trying out took different forms. Sam played some of the video footage he had gathered when working at the behest of traditional owners as they evidenced their connection to sacred sites. Each clip showing different stages of editing and differing enactments of places and authority. Christine had images of the Chinese artefact that had been found in the roots of a Banyan tree, and worked through archive and story to reveal its contested providence. And I had my first run through of the way in which our participative involvements with Gurambai/Rapid Creek might appear in a university setting. The crowd was a friendly one, and I knew there was a certain sound, feel and tonality that I wanted to be present. It was the muted tones and colours of the sands at the saltwater end of the creek, mixed with and carried through some of the vibrant oranges and greens of the pandanus nuts and fronds from the upper reaches of the creek. I had gathered together different objects and materials, some gathered along the creek, some produced in our previous writing up of TopEndSTS forays. I felt there needed to be a mix of materialities of the creek (such as pandanus nuts) as well as images, sounds and texts (in the form of maps, zines, historical stories all created by TopEndSTSers) all appearing their together side by side, but without one particular form dominating. So that those meeting the display could also sense the crunch of footfall and the flow of the water, I played on a loop a soundtrack of a past creek walk and added a rolling set of slides showing us in strange positions, holding sound recorders up to listen to the sounds of swamps, or flows of water over weirs. In the middle I placed a small screen with the footage of swimming fish on it, and invited people to try the inefficient mapping. Here, while the creek seemed to seep through my conversation as I narrated the various things on the table as practices, or doings, of the creek, this interactive element with the fish didn’t really take off. But I liked it, and decided to keep it in the show (so to speak) when I went to Canberra.

iii. At AusSTS

The atmosphere at the M&D session at ANU was lively. We were in a large hall with two big desks allocated for each presenter and plenty of room for the audience to move around and visit each stall. I had brought with me many of the same materials as in the trial run, and hoped again that some of the sound, texture and liveliness of the creek would seep through. In the first presentation I had largely addressed the audience, somehow starting in the middle of a story in which objects and practices, knowers and knowns emerged together. Here, there were many different conversations, each starting somewhere else, with these questioners drawing out different tales from me each time as I narrated the stall, our work and directed by contingent involvements in place. The fish were their again swimming on the small screen, and here, somewhat primed to be involved people started to have a go at the inefficient mapping exercise. On the table were coloured pencils and small pieces of paper. People would ask about the fish and I would explain the inefficient mapping Kelly Lee had introduced to us. ‘Just watch the fish’, I would say. ‘Follow it with your hand as you draw its route with your pencil. When it reaches the edge of the screen, pick up a new one’. At one stage there were 4-5 heads down, faces transfixed, focussed and drawing, seemingly wholly consumed with their task. Then one person jumped up and exclaimed ‘I think I drew the same fish twice’ and he showed me his paper, with two paths tracing the same odd trajectory, and mirroring each other. We both smiled because it seemed somehow something momentous had happened, although we weren’t too sure what. Then he placed his name and date on the paper and left it behind. Others started doing the same and before long a small pile of inefficient maps had gathered on the table. Patterns and structuring were starting to emerge, seemingly unbidden and of their own accord. A new, just marginally visible epistemic routine; practices in which moving fish, a video recording, pencils, paper, an archive of new documents and STS experiencer-knowers had somehow arisen in the setting of AusSTS and the modern university.

Reflecting on these stories…

In the first of these ‘university’ stories, it was the place which seemed to somehow come through in the telling of stories and showing of objects. In the second, it was these new routines which took centre stage as I narrated the willing involvement of STS scholars in an activity which they entered into as completely incompetent knowers, and yet by doing so something interesting occurred.

Folding these two ‘university’ settings together with the setting of sitting beside Gurambai/ Rapid Creek, helps this strange act of the emergence of new epistemic routines within university settings to become visible. This enfolding has let me see and draw attention to new routines momentarily visible, as ongoing engagements of bodies and creeks were sustained.

It may be a testament to the openness of STS as a particular scholarly field that such novel practices and routines might so easily and willingly appear. However, in holding these stories together here, I also effect a moment of evidencing the possibility that different practices and figurations of knowers and knowns *could* appear and be engaged within the modern academy. And it is perhaps THIS story that I should share back to Donna and Lorraine.

Where are you sitting now – at a desk in a university? Would you like to have a go?

Here are the instructions…

- Have with you a piece of paper and a pencil or pen

- Pick one of the fish

- Look at the fish (not the paper) and follow its movement as it swims

- When it reaches the edge of the screen, stop drawing and pick up a new fish